Amazing Facts About Wildlife

Australia, bushfires and megafauna

Introducing elephants has been suggested as a solution to the crisis down under, says S.Ananthanaryanan.

Bush fires in Australia are like the seasons. Vast tracts are destroyed by fire every year, starting in the North in the winter and moving to the South in the summer. Every few years the raging comes to peak and the fires of 7th Feb 2009, now known as Black

Saturday, were the deadliest on record – 400,000 hectares destroyed, 173 people dead.

David Bowman, professor of environmental change biology at the School for Plant Science, University of Tasmania, Australia, in a Comment in Nature, has reviewed the suggestion of introducing mammoth species to restore ecological balance and control fires.

Extinction of mammoths

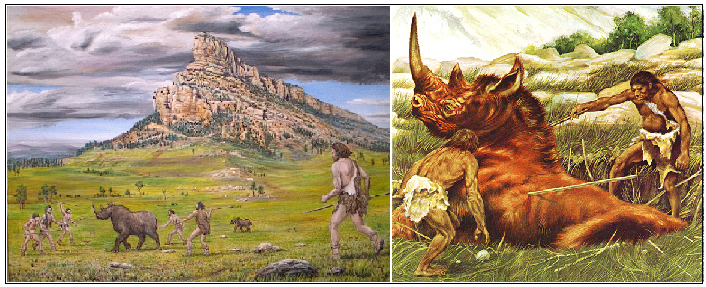

Large, plant eating animals that ranged the earth went extinct around 50,000 to 12,000 years ago, when humans appeared on the scene. While climate changes also played a role, it was perhaps the humans, who could target the mammoths with spears, arrows and slings,

who pushed the mammoths out of their feeding grounds and into extinction. Smaller animals, which presented difficult targets and reproduced faster were able to survive.

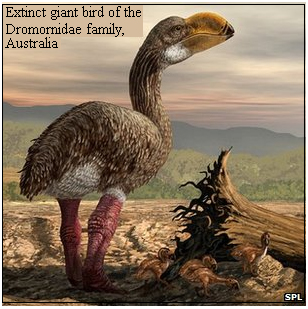

The extinction of large animals affected the flora, with larger bushes and grasses being left to grow wild. In Australia, the extinction of animals was of giant, Kangaroo-like animals, giant lizards and large, flightless birds. The food chain – of large plants

being eaten and large dung and carcasses to recycle nutrients - broke down and the landscape changed. The disappearance of the mammoths created breaks in the continuity of the food web, or niches in the ecosystem, and these were left unoccupied. The animal

species which disappeared were replaced by smaller species, pigs, goats, cattle, horses, donkeys, camels, buffalo and deer, and their predators, which include the Dingo or Australian wild dog, and the new entrants have been rebuilding the ecosystem. But the

larger bushes have been left to grow unchecked, for animals evolve but vegetation takes longer to adapt and the Australian ecology has stayed out of balance.

Paul S Martin, who was a geoscientist at the University of Arizona, said that ecological communities in North America did not function in the absence of megafauna, because much of the native flora and fauna cannot turn around the path of evolution which progressed

in the presence large mammals. Things were aggravated in Australia by foreign grasses and animals species, which came with Europeans and threaten native strains and compete for resources. The early human communities had followed practices of burning patches

of bushland for cultivation. But with the loss of aboriginal peoples and traditions, this practice has stopped and the growth of wild flora is unchecked. The aboriginal practice of hunting also kept down the population of smaller, wild animals. But this is

no longer the case and the animals cause more environment degradation.

The Australian Government goes to great expense to deal with the problems. The methods include chemicals to control of wild grasses and barriers to the spread of fires, which are expensive and only partly effective. To check animal menace, there has been poisoning

of the Dingo populations and even crude measures like tracking wild buffalo by radio collars and helicopter, to shoot members of herds. The killing of Dingo disrupts their social structure and eliminates an effective way to control smaller animals, like foxes,

which were introduced by European settlers, and the pig and rabbit population, which attack vegetation and cause erosion and habitat destruction. Ironically it is wildlife and vegetation that are the risk factor for the environment in Australia.

Restoring balance

Professor David Bowman says this approach of taming an eco-structure gone wrong may never arrive at a solution. He has proposed measures that would go the root of the problem, which is to stabilize the food web. The two problems, of animals running amuck and

the flammable grasses growing wild, he says, need to be tackled by predators to control the animal population and by large herbivores to check the grasslands. Stopping poisoning of the Dingo would by itself make for predation of the smaller animals. For larger

species, like the buffalo, Prof Bowman suggests making use of the community of aboriginal hunters in Australia. “Ranger programmes that enable indigenous people to return to their roots — by hunting buffalo or managing natural resources — have been shown to

have social and health benefits for this disadvantaged sector of the Australian community”, says, Prof Bowman.

As for the menace of bushland fires, he notes that a major cause is the growth of Gamba grass, a giant African grass that has invaded Australian plains. The grass “is too big for marsupial grazers (kangaroos) and for cattle and buffalo, but it is a great meal

for elephants and rhinoceroses,” Prof Bowman writes. “The idea of introducing elephants may seem absurd, but the only other methods likely to control Gamba grass involve using chemicals or physically clearing the land, which would destroy the habitat. Using

mega-herbivores may ultimately be more practical and cost-effective, and it would help to conserve animals that are threatened by poaching in their native environments.”

The idea is not far different from the ‘rewilding’ inititatives in North America. It has been noted that most living megafauna are threatened or endangered. But they continue to influence the communities they occupy, as the communities evolved in the presence

of the same large animals. Re-introducing into the environment the mammoths that lived in prehistoric times, or their surviving cousins, could invigorate the ‘evolutionary potential’ of these species and also fill the ‘ecological niches’ that have been vacant,.

The idea in North America is a ‘Pleistocene rewilding’ or recreation of the environment of over 10,000 year ago, with camels and lions, and it has its share of critics who argue that the earth is now not the same as it was during the Pleistocene.

Nor is Prof Bowman without critics in Australia.” Elephants could become the ‘10-tonne cane toads’ of the Australian outback if they were introduced to control invasive grasses,” says Patrick O’Leary of the Pew Environment Group, an active think tank and action

agency. But Prof Bowman is not blind to the challenges his idea would pose – and he cites resources, “we could adopt management methods from game parks and reserves, such as building fences, regulating the availability of water and food, and con¬trolling breeding

and hunting”, he says. Using animals to deal with problems that otherwise call for huge investments and energy use could be effective and green at the same time.

[the writer can be contacted at simplescience@gmail.com]

|