The boma in Chattisgarh’s Udanti Wildlife Sanctuary has a unique resident- Asha, one of Central India’s last wild buffaloes. At first glance, she looks strikingly similar to her domestic kin, but a closer inspection reveals the massive spread of her horns

and huge bulk, which are unmistakeable characteristics of the wild buffalo.

Asha’s proud ancestors would once have roamed across much of Central India and Northeastern India. The eminent hunter-naturalist Dunbar-Brander, writing in the 1920’s, wrote of their abundance in the forests east of Balaghat, with their biggest stronghold

being Bastar.

Unfortunately, the wild buffalo’s range and population have undergone a massive contraction since. A survey in 2007 by the NGO

Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), estimated their total population in Central India as being less than 50 individuals. Indravati, home to the largest population ( of about 25-30 individuals) ,

was in the grip in left-wing extremism, and hence, no conservation programme could be taken up there. Udanti in Raipur district was found to have 7 wild buffaloes, of which only 1 was female. The decline has been particularly steep in recent times, since in

1993, Chattisgarh itself was believed to be home to around 250 buffaloes, with both Indravati and Udanti having approximately 100 individuals each. Healthy populations of these giant bovines continue to exist in quite a few Protected Areas in the Northeast,

such as Kaziranga, Manas and Dibru Saikhowa in Assam,

Balpakram in Meghalaya and Dayang Ering in Arunachal Pradesh.

A wild buffalo with its calf in Kaziranga National Park.

Pic : alamy.com

However, many of the Northeast’s 3000-3500 wild buffaloes are believed to have been adversely affected by interbreeding with their domestic kin, and the remaining populations are also threatened by the destruction of their wet grassland habitat and poaching.

Asha, with one of her calves, at Udanti.

Pic : Dr R.P Mishra, WTI

WTI, with the assistance of the Chattisgarh Government, swung into action immediately. A “Wild Buffalo Conservation Project” was framed. Conservation initiatives could be undertaken only in Udanti, as it was the only habitat of wild buffaloes which was free

of naxal violence at that time (sadly, naxals have extended their control over much of udanti, and neighbouring sitanadi, since 2009-10. However, attempts to conserve the wild buffalo continue).

Given the very low population in Udanti, conservationists were determined to prevent any unnatural deaths, which could lead to the extinction of the population there. A “boma”- an artificial enclosure was constructed for the last female buffalo of Udanti,

aptly named “Asha”, or hope. She has given birth four times since. Conservationists, however, could truly rejoice only when she gave birth to a female calf, named “Kiran” for the first time earlier this year. Her previous three calves had all been male. The

male calves grew up in the boma with her, before joining the herd, which spends most of its time in an adjoining grassland, with some boisterous males frequently visiting the adjoining villages to mate with the female domestic buffaloes there.

One of Asha’s calves gets a health check-up.

Pic : Dr R.P Mishra, WTI

Not wanting to take any chances, Karnal-based NDRI (National Dairy Research Institute) cloned Asha in January 2015, producing a female calf named “Deepasha”. These three females represent the last hope for Chattisgarh’s beleaguered wild buffaloes. Asha herself

is 13 years old, and a female wild buffalo is normally reproductively viable for about 15-17 years of her lifespan, which is usually 20-22 years.

Even though administrative apathy and a steady rise in naxal presence in the surrounding forests have stymied initiatives, several attempts have nonetheless been made to preserve the buffaloes of Udanti. These involve the inoculation of livestock residing

in fringe villages, the deweeding of grasslands, and the providing of incentives to villagers encouraging them to sell off domestic buffaloes, so that interbreeding between domestic and wild buffaloes, leading to a contamination in the genetic stock of the

latter doesn’t occur. Attempts are also being made to procure genetically pure wild buffalos from the Northeast to boost Udanti’s tiny population.

In spite of so many measures, however, the path ahead is still treacherous.

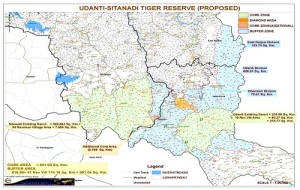

In 2009, a tiger reserve, covering 1,842 sq. km (with a core area of 851 sq. km) was eked out of Udanti and adjoining Sitanadi wildlife sanctuary. The Udanti-Sitanadi tiger reserve suffers from several management lacunae, however. These include a highly

complex administrative set-up which is not conducive to tiger conservation, with the Field Director’s office being located in distant Raipur. Moreover, protection infrastructure such as anti-poaching camps and vehicles for patrolling, is severely lacking.

The DFO’s managing these sanctuaries are often burdened with non-wildlife conservation related tasks, dealing with the management of the surrounding territorial forests. A massive overhaul of the protection mechanisms currently in place need to be carried

out by the State Government.

This will be very hard to carry out, however, given the ongoing naxal insurgency in the landscape. Udanti-Sitanadi should not be written off, however. Along with the contiguous Sunabeda-Khariar forests in western Odisha, it forms part of a compact forest

block extending over 3000 sq. km, which serves as an important habitat for many species of Central Indian flora and fauna. Proposals to denotify such “lesser” forests are based on a poor understanding of their ecological potential, and should not be acted

upon.

Tigers with cubs have been reported from Udanti and surrounding forests in recent times, and, for the first time, a tiger was camera trapped in 2014, an event which put to rest niggling doubts regarding the presence of tigers in the landscape.

A map of the Udanti-Sitanadi Tiger Reserve.

Pic : cgforest.com(Chhatisgarh Forest Department)

Attempts have also been made to conserve the other viable population of wild buffaloes in Central India, in the Indravati landscape. Indravati itself may be out of bounds to the Forest Department, but neighbouring Kolamarka, in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli

district, frequently plays host to a couple of herds. A 181 sq. km area in Kolamarka was declared a conservation reserve in 2013, for the conservation of wild buffaloes. Inspite of recurring incidents of naxal violence, a dedicated team, led by RFO Atul Deokar,

have been diligently monitoring the wildlife of the region, while undertaking numerous conservation initiatives with the help of the local villagers. Kolamarka is also an important habitat for Maharashtra’s state animal, the Indian giant squirrel (

Ratufa Indica). To sustain these initiatives, support from the State Government is key. Kolamarka’s forests are threatened by habitat destruction and poaching, and conserving the small wild buffalo population here (estimated at around 10-15 individuals),

will be a stiff challenge.

“Treasures of Kolamarka”-a book detailing the biodiversity of Kolamarka conservation reserve in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli and is a product of the untiring efforts of RFO Atul Deokar and his team.

Pic : RFO Atul Deokar

Of late, the Central Government has also taken an interest in wild buffalo conservation, with the buffalo being one of the five target species for which recovery programmes have been implemented. Moving these plans from the cramped confines of the bureaucrat’s

office to the field in the badlands of Udanti-Sitanadi is of the utmost essence.

The Central Indian wild buffalo has never received the same amount of conservation support as the tiger or the elephant, with the result that it is poised on the brink of extinction in a region that was once its historical stronghold.

Asha, the last adult female of Udanti, embodies the hope that the noble bovine will recover from the brink of extinction, and reclaim those forests which they once lorded over.