Staying together without a leader

Independent individuals sometimes move in concert without being conducted, says S.Ananthanarayanan.

A well-known instance is the collective behaviour which is seen in groups of insects, birds, fish, even bacteria. While there are no indicators that individual members of the groups are aware or conscious of more than a few neighbours, the whole group

self-organises with coordination and cohesiveness, as if enclosed in an envelope, or a containing surface, and the group moves like a single, sentient being.

The phenomenon is of interest both in the study of the animal kingdom as well as one to mimic while managing groups of machines, or in robotics. A step to help understand the mechanism that translates the relationship among a handful of individuals into

orchestration of the whole assembly may be finding the smallest size of the group that shows such behaviour. James G. Puckett and Nicholas T. Ouellette from Yale University, Connecticut, have examined this question and they report in Interface, the journal

of the Royal Society, that it takes just ten individuals of one species of insect to act essentially in the same way as a swarm of many more.

Swarming behaviour is seen most markedly in the movement of hordes of locusts, in the coordinated, short flight of thousands of birds, usually from one large perching area, like a set of trees, to another, and in shoals of fish. Bacteria are found, when

present in sufficient numbers, to slide en-masse across surfaces and even microscopic plants, like phytoplankton, form themselves into vast rafts called ‘blooms’. The characteristic is that the individuals in the groups are self-propelled and are not subject

to any centralised control. “The group-level dynamics emerge spontaneously as a consequence of the low-level interactions between individuals,” Puckett and Oullette say in the paper.

A mathematical model of a swarm could consist of several basic units, capable of motion, placed together and subject to simple rules. The rules, for instance, could be that a unit should move the same way as its neighbour and stay close to neighbours,

and yet a little away, so that it does not touch a neighbour. It is easy to imagine that if the members of a large group all follow these rules, there will be random shuffling and lead to general movement of the group in some direction, which may veer and

swerve as individuals make their decisions to keep following the rules.

Another example of large numbers of individual particles following specific rules in bulk is that of the molecules of a gas. Here, the thermodynamic equilibrium, which is the pressure and volume, given the temperature, is decided by the rules of statistics,

of the number of different, equivalent combinations there can be of the molecules of the gas distributing themselves in, for a given total energy. It works out that the distribution where the gas has the same pressure and temperature at all parts of the container

is the distribution that can be arrived at in the most number of ways, and this distribution becomes more likely when the number of molecules increases. This is then the actual distribution, as different ways, like with the molecules on one side of the container

moving faster than on the other side, in even a small volume of gas, are vanishingly unlikely.

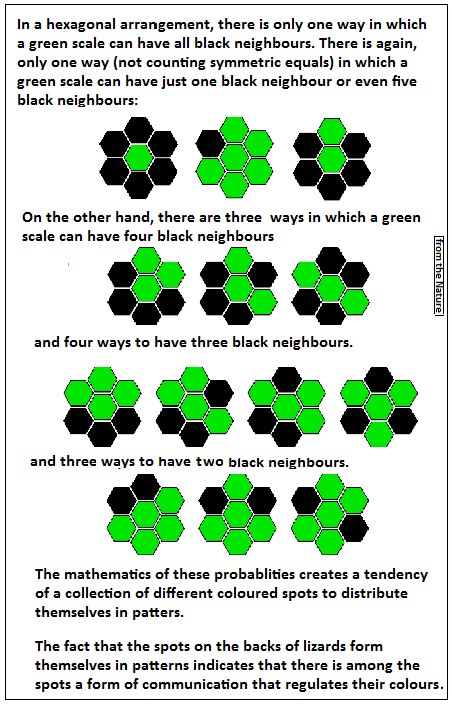

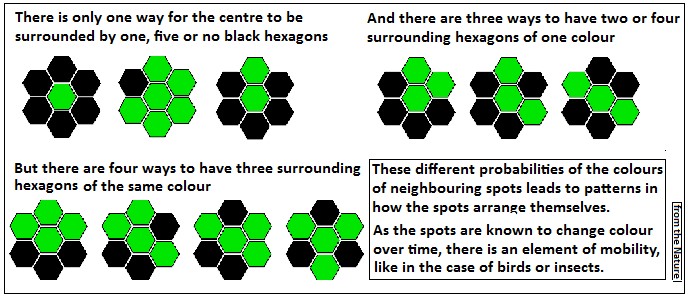

This kind of statistical thinking helps explain certain other natural phenomena of distribution of independent units along patterns, like the spots on some lizard species. The spots are found to change colour, over time, in a way that depends on the colour

of neighbouring spots. Now, if the spots are viewed to be distributed in hexagons, it can be shown that the most likely neighbourhood is one with three neighbours of a different colour. This then becomes the rule for each spot and each of the neighbours to

follow, and the result is a ‘labyrinthine’ pattern whose origin it is difficult to explain in any other way.

The units in swarms of animals, however, are capable of self-propulsion, unlike molecules whose speed and direction depends on collisions with other molecules. Collective movements of animals hence cannot be treated in a straightforward statistical way

like with a gas, but can still be viewed as the ‘large number’ tendency as more and more self-propelled and mutually interacting units come together. When the group is very large, the paper says, it is reasonable to suppose that one part of the swarm is not

different from another and that the group behaviour represents a state that is shared by all units. This assumption, however, is not valid when the group is small and small groups would not have the cohesion and resilience of large groups. Discovering how

large a group needs to be before it reaches the stage when adding numbers does not bring about appreciable change would help understand the ‘low number’ behaviour of groups, Puckett and Oullette say in the paper. This would impact bio-inspired engineering

applications by setting the smallest number that must be there for group behaviour to emerge, they say.

Another way of looking at swarm behaviour is that the disorganised movement of smaller groups of individuals appears to become ordered and follow a pattern when the group reaches a threshold number. The transition is then seen as a kind of ‘phase change’,

like we see when water vapour condenses to liquid or when liquid water freezes to ice. Finding the threshold numbers for swarming would show the stage at which uniting effects of the rules of interaction overcome the fissiparous nature of groups of individuals,

and hence keep the group together.

Puckett and Oullette considered the movements of swarms of midges, the annoying collection of flying insects that form a cloud around people’s heads when they are out in the open. These swarms do not move over distances, like swarms of fish or birds, but

the midges, in rapid motion themselves, stay together over a limited defined area, as a group.

“As collisions are disadvantageous and the sharp manoeuvres required to avoid a collision when two individuals come close together are energetically costly….. the midges tend to arrange themselves to maintain some empty space in their local neighbourhood,”

the researchers say. The researchers then used rapid, high speed photographs of 344 swarms of midges in motion, to analyse the changes in statistical features of the midges’ local surroundings as the groups changed in size. With groups ranging from a single

midge to groups of sixty midges, a main feature of analysis was of the average volume, as a fraction of the volume of the swarm, that each midge occupied in its flight, on the average, over a period.

The study has shown that while the statistics change as the number of participants increases, they settle down to a steady figure at the level of just ten individuals. Thus, while on midge may roam freely around a central average position, two midges are

somewhat more united and three midges even more so. But when we reach ten midges, they form a swarm that stays basically unchanged as the numbers increase, even to thousands.

The study may the first time that individuals flying in a three-dimensional swarm have been tracked, to reveal how collective behaviour emerges as the swarm size is increased.

Do respond to : response@simplescience.in